The Ancient and the Ultimate

Fifty years after Asimov's essay on books, we still strive for the ultimate while prizing the ancient.

Whenever I see so-called improvements in e-books, I am wont to recall one of my favorite Isaac Asimov science essays, “The Ancient and the Ultimate1,” from which this newsletter takes its name. The essay is an attempt to defend the noble, humble book, against improvements in technology, for instance, the VCR cassette, recently introduced at the time the essay was written back in 1973. Cassettes like these would eventually make books obsolete. Asimov took that argument to its natural conclusion, arguing about more and more improvements that could made until eventually, what you found you were holding was… a noble, humble book.

E-books are purportedly an improvement that Asimov never considered. His essay, I recall, focused on a single book, while a device like a Kindle (or an iPad) can contain an entire library of books. Moreover, an e-book reader provides additional flexibility over a paper book: one can tailor the font sizes, and background colors; one can easily search for text. While I love this flexibility, I find it difficult to engage with an e-book the way that I do with paper books. I tend to make books my own. I mark them up. I underline some passages, circle others. I argue and question in the margins. I make notes of ideas and thoughts (and even other books) to pursue. This is a clunky and unnatural process in an e-book.

One can highlight and add notes, but doesn’t feel the same, nor is it as easy or spontaneous as on paper, at least for my aging hands. One has to dexterously highlight a passage, then tap to add a note, then use a clumsy virtual keyboard to type out the note, and in doing so, lose spontaneity of thought. And when that is done, all one sees is the highlighted passage with a footnote marker with no other context. One has to tap the note marker see the note. I prefer seeing everything, all of my highlights, notes, and other scribblings spread across the page in one messy jaunt.

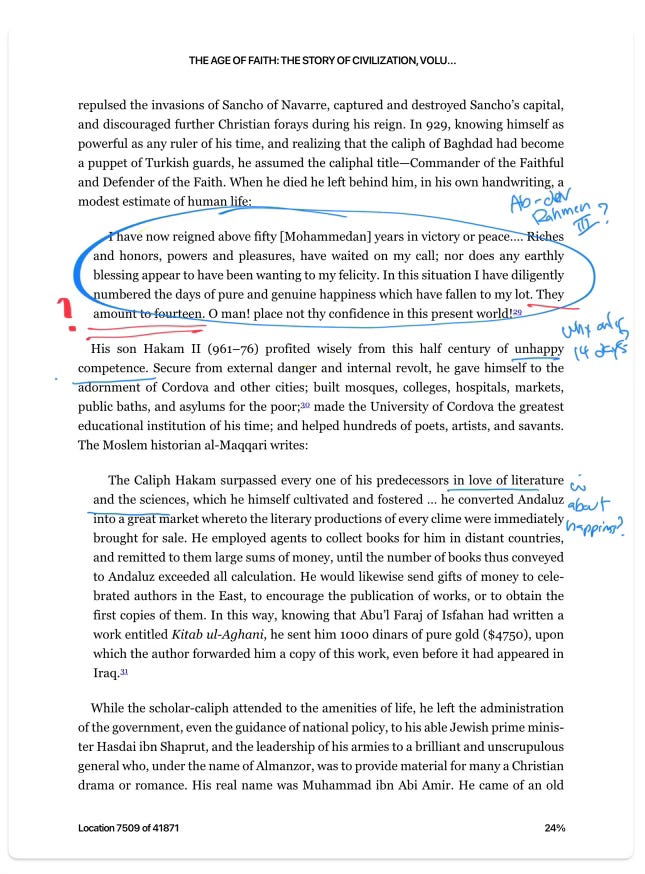

What irks me is that what I do on the printed page should be readily achievable on the digital page. Here is a page from my paper copy of The Age of Faith by Will Durant:

These annotations would appear as highlights and note markers on the Kindle edition of the book. Some of the spontaneity of the notes and their positions relative to one another would be lost even if the words were the same. The presentation is an important part of the way I jot my notes.

Now, I’ve been a software developer of one form or another for four decades and I can think of no reason, with today’s technology, why a digital book can’t reproduce the experience above. Here, for instance, is a mock-up of what I have in mind2:

This seems to be a readily achievable design, at least in the app version of the Kindle (I imagine it is more of a challenge in an e-ink device). This can be rendered as a scalable layer over an existing digital page. I say scalable because the fonts and font sizes on a Kindle are scalable, and you’d want your notes and highlights to scale with the text.

There are downsides to this, I suppose. For one thing, digital highlights and notes captured as text through a virtual keyboard are searchable, where as the annotations above are not as readily searchable (although with improvements in machine-learning, I suspect this will change in the near-future).

To be fair, it seems as if the Kindle is moving slowly in this direction. Their recent release of the Kindle Scribe allows for handwritten notes, but the display of those notes still doesn’t match what I am looking for above. E-books, it seems to me, still have a long way to go to match the elegance of design and usability of the noble, humble paper book. In this regard, Asimov’s essay still rings true to me, more than a half-century after it was first published. In that time, we have made good strides toward the ultimate book design, and yet, it is the ancient that still wins out.

See The Tragedy of the Moon by Isaac Asimov, Doubleday, 1973

I’ve been fascinated by this quote ever since I first encountered it in the second volume of Isaac Asimov’s autobiography, In Joy Still Felt (Doubleday, 1980).

Off topic but my iPad does not fill me with the same joy as the smell of a vintage book

I think you can do this with the reMarkable device