I’ve gone through a spate of biographies1 so far this year, and whenever I read one, I frequently find myself experiencing the same reactions: envy and grief.

When I read a biography, I find that I am so fascinated by the subject at hand that, with few exceptions2, I mentally kick myself and wonder why I didn’t go into that particular field. Reading a biography of Red Smith3, for instance, I came away wondering why I hadn’t stuck with journalism and gone on to become a baseball writer. Or what about Stephanie Gorton’s outstanding biography of Ida Tarbell4? I read that and wanted to be a muckraker. Reading William Poundstone’s biography of Carl Sagan5 reminded me of how much I wanted to be an astronomer when I was a kid.

This holds true for more than just biographies. Reading Stephen Jay Gould’s essay collections6 from his This View of Life column in Natural History made me wish I’d studied paleontology. Reading Andrew Chaikin’s A Man on the Moon in the late 1990s made me want to be an astronaut, and I actually started to look into what it would take, up-to, and including getting my private pilot’s license7.

At some point, it occurred to me that we are missing a big opportunity by not introducing kids to biographies at a much earlier age. Benjamin Disraeli said: “Read no history8; nothing but biography, for that is life without theory.” Want to know what it is like to be a rock star? Read Bruce Springsteen’s memoir, Born to Run, which is excellent and paints a realistic picture of the mixture of skill and luck involved in the creative arts. Want to prepare for a political career? You can do no better than one of the many biographies9 of John Quincy Adams, who had an extensive political resume before becoming president, and who didn’t rest on his laurels in retirement, serving the rest of his life in the House of Representatives. Or what about life in the biotechnologies? Check out Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jennifer Doudna, The Code Breaker. You get the idea.

And yet, that envy is tempered by the grief I often experience when a biography ends. During the time I’m reading the book, I feel like I am living the life—or perhaps, borrowing the life—,following around the subject, getting to know them personally, marveling at their achievements10, or horrified by their actions11. And yet the end is inevitable, and often I find myself grief-stricken when as the pages, like the years, run out.

I’ve thought about this recently as I’ve made my way through several biographies and it occurs to me that part of this stems from the compressibility of life. Reading, I experience both an accelerated and compressed life, and when it is over, I feel sad. There is also a haunting feeling that moves in the shadowy background of each biography I read. We all know death is inevitable, but when we read a biography, we often know when and how that death will come, even before we get to the ending. It is like spending time getting to know someone, when all the while, I hold back this secret from them.

I know I am not the only person who reacts this way to biographies. I remember reading as passage in Isaac Asimov’s autobiography where he and his wife, Janet, were visiting the University of Virginia while Janet happened to be reading a biography of Thomas Jefferson. Asimov wrote (in a footnote):

When she finished the biography, she came to me in tears, saying, “Jefferson just died.” I put my arms around her and said, “There, there, he’s eighty-three years old and went quietly.”12

Asimov never mentions which Jefferson biography she was reading, but I know I felt that way when I came to the end of Dumas Malone’s 6-volume biography of Thomas Jefferson13. I mean, how can you grow up with a person for that long and not feel sad at the end? Reading a biography, for me, is like living a life between Monday and Friday14. I am sometimes reminded of that episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, “The Inner Light,” where Picard experiences an entire lifetime in 15 minutes.

I’ve come to realize that part of the grief is not necessarily about the subject of the biography, but about me. How compressible will my life turn out to be? And how lossy is that compression? I have diaries going back almost 30 years, and yet I’m no Samuel Pepys or John Quincy Adams in the ardor of my recordings.

There is something powerful about seeing a life in glance, captured between the pages of a book, holding it in my hand, and starting to read with the ending a forgone conclusion. But I push that conclusion out of my mind, just as I do as I make my own way through life, glancing only furtively toward the end, but always with the knowledge that end is coming. There are fewer pages ahead than behind.

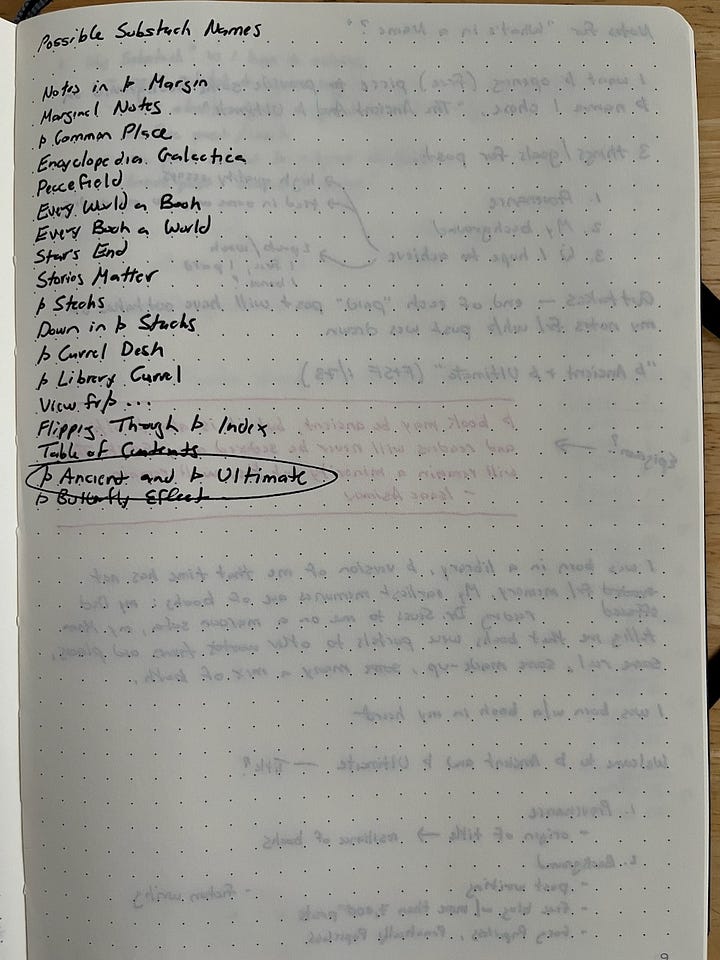

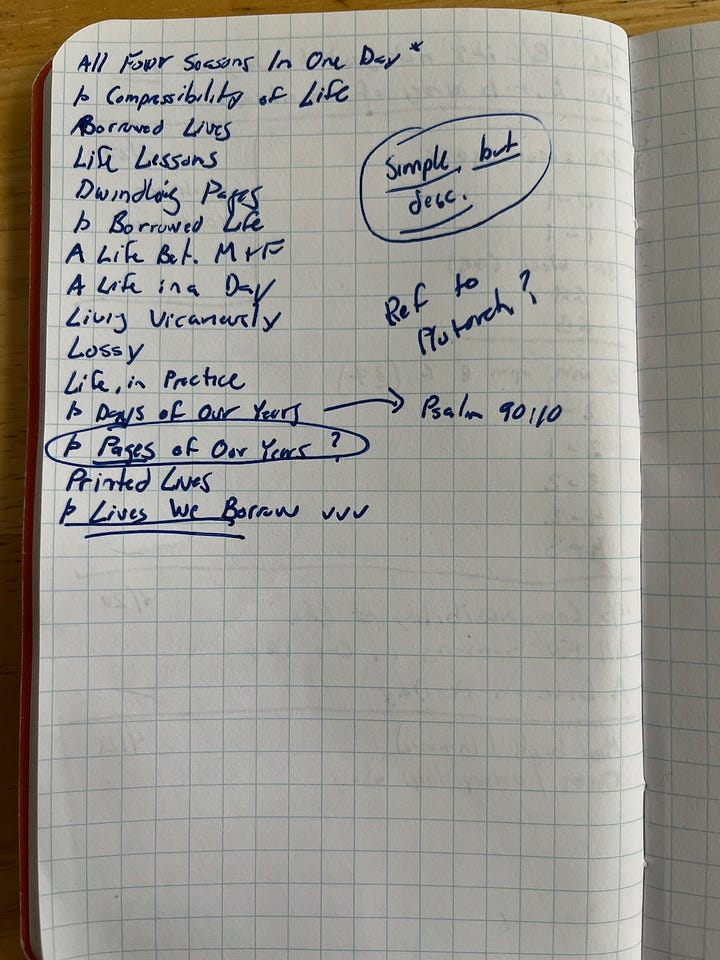

Outtakes

I was revising this piece up until 4 minutes before it went live. Here are some notes that helped construct this post—and this newsletter.

I’ve read (or re-read) 8 biographies so far this year, so I’ve been encountering these feelings quite a bit.

Although I’ve read many biographies of politicians, I’ve never wanted to be one myself, despite holding a degree in political science.

Red: The Life & Times of a Great American Writer by Ira Berkow, University of Nebraska Press, 2007

Citizen Reporter: S.S. McLure, Ida Tarbell, and the Magazine That Rewrote America by Stephanie Gorton, Ecco/HarperCollins, 2020

Carl Sagan: A Life in the Cosmos by William Poundstone, Henry Holt, 1999.

I went through all of the collections in the series in fairly rapid succession in 2023. They are some of the most engaging (and challenging!) essays I’ve come across. Similar in approach, but different in style from Isaac Asimov’s science essays from the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. This alone is a topic worthy of its own post.

It didn’t take long for me to discover how remarkably under-qualified I was. The people who I saw being selected for astronaut classes were the overachievers of overachievers. It seemed to me that the typical biography was something like: “B.S. Computer Science with a Masters in Engineering and a Ph.D. in Astrophysics, with an MD on the side. 2,400 hours of flight time in multiple types of jet aircraft; avid rock climber, and deep-sea diver.”

I disagree here. Read history, too.

I’ve read John Quincy Adams: American Visionary by Fred Kaplan, Harper Collins, 2014; John Quincy Adams: Militant Spirit by James Traub, Basic Books, 2016; and more recently, The Problem of Democracy: The Presidents Adams Confront of the Cult of Personality by Nancy Isenburg and Andrew Burstein, Viking, 2019. And later this summer, I’m looking forward to a new one: John Quincy Adams by Randall Woods, Dutton, 2024.

Leonardo da Vinci, for instance. See Walter Isaacson’s Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson, Simon & Schuster, 2017.

Like Robert Moses as portrayed in The Power Broker by Robert A. Caro, Vintage Books, 1975. I had to set that book aside several times while reading it because Moses made me so mad.

In Joy Still Felt: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954-1978 by Isaac Asimov, Doubleday, 1980.

Jefferson and His Time: The Virginian is the first book in the series.

Sometimes longer. It took me the entire month between mid-August and mid-September 2014 to get through the 3-volumes of William Manchester’s biography of Winston Churchill, The Last Lion, Little Brown, 1983.